“I don’t want the public to see the world they live in while they’re in the Park (Disneyland). I want to feel they’re in another world.”

–Walt Disney

How do theme parks place us in a fictional world? Is this achieved by creating attractions that somehow work to tell a story?

In a previous post, also about DisneyWorld attractions, I tackled these questions by proposing a distinction between world-telling and what we commonly call storytelling.

When a work–a novel, a movie, a comic, or a ride–tells a story, it prompts us to build in our minds a sequence of fictional events, using memory and inference to derive from the sequence a causal chain (i.e., a sense of how one thing leads to another, and another, the ultimate source of our experience of anticipation, suspense, and surprise).

But when a work narrates a world, it does something different. It prompts us to combine memory and inference with imagination, to envision the cultures and spaces which shape these events, and in which these events transpire.

Some critics say that when worlds are told to us we infer and imagine a mythos, topos, and ethos–an idea of where the world came from, the spaces that comprise that world, and the behaviors and values of the world. I break that down even further.

As we take in a movie or experience a theme park attraction of the level of detail that we find at DisneyWorld, we imagine power relations (typical tensions within the world), rules (the capacities of those who inhabit the world), cultures (the languages, customs, technologies, and art forms characteristic of the world), and places (the look, sound, and feel of the locations that comprise the world).

Imagining these things triggers additional imaginings: we register environmental scale; we supply perceptions when information about the world is sparse; we shift perspectives (i.e., allow ourselves to “try on” the points of view of various fictional agents inhabiting the world); and we find ourselves adopting a conative attitude–a wish to occupy this realm, to live vicariously through the fictional agents who do.

Storytelling and world-telling are distinct experiences of media, then. But some media combine these experiences.

A DisneyWorld theme park attraction might seem like a poor medium for storytelling and a strong medium for world-telling. Strolling about in sweltering heat, waiting in long queues, dodging other lollygagging patrons, and juggling children, backpacks, water bottles and big turkey legs, most visitors probably aren’t in the best frame of mind to take in even an elemental plot. Theme parks are rife with what psychologists call distraction stimuli. Most visitors will only have the attention to form quick and broad impressions about the worlds they’re brushing past.

But I think the art and craft of DisneyWorld imagineering–the creation of these attractions–assumes otherwise. My impression from looking closely at the design of these attractions and the parks as a whole is that they presuppose a patron who, even amongst these distractions, is able to perform some fairly complex entertainment- or thrill-oriented tasks, like picking out relatively elaborate stories and imagining relatively detailed worlds–or picking out the stories built into these detailed worlds.

In other words, some DisneyWorld attractions are layered. They are designed with one layer of experience–a world-telling one–which contains or supports a second layer–a storytelling one. By taking in the details–the detailed details–of the fictional world, we begin to note how this world contains the rudiments of a plot. Plot events emerge from the world we experience (fig. 1). And with reflection, we can connect these events to form a chain–an ongoing story experience.

Sometimes that plot is affixed to the world of a single attraction, as in the case of the now-closed Splash Mountain ride (view a walk-through here). Sometimes that plot is affixed to the world of an entire land within a theme park, as in the case of Pandora, the World of Avatar (view a walk-through of the park above, and of the attraction, Avatar: Flight of Passage here). In fact, in my previous post on DisneyWorld, I show how the land and the ride conspire to tell a story, and in doing so, they offer visitors a sequel to the 2009 Avatar film. The film and the theme park, when taken together, tell a transmedia story.

The newly opened TRON: Lightcycle/Run (2023) combines the Splash Mountain and Pandora strategies, but its storytelling is far more suppressed than either one. It tells its story within a single attraction, and that story emerges as a sequel to the 2010 film, TRON: Legacy, but the storytelling of TRON: Lightcycle/Run is subsumed under a much more dominant world-telling encounter for the visitor.

Discerning the story being told requires some effort. Here’s what I mean.

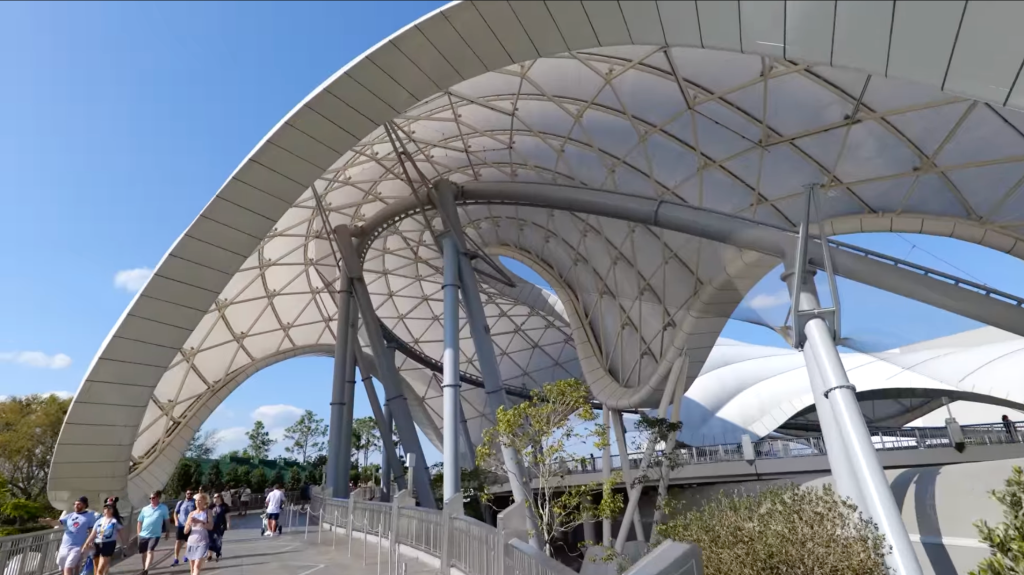

From the moment we walk up the long ramp and approach the outdoor concourse of TRON: Lightcycle/Run, our mind is being cued to attend to the world we about to enter–and to its feel. This attraction creates the wonderful impression that we’re entering a space of unfamiliar futurity and unsettling risk.

Immediately, the strangeness of the architecture situates us in a space and time; this isn’t our world (fig. 2). The track of the rollercoaster scales beneath a grand, spiroid canopy. No story is being told here–no events of a plot are being relayed. Instead, the design evokes in us a sense of speed and of technology that, in this world, defies gravity. We begin to shift perspectives–to anticipate what it will be like for us to fly through the structure at high speeds.

As we continue up the ramp, the design–the exposed sights and amplified sounds of screaming patrons rushing past us on their rollercoaster cars–continues to foster a perspective-shifting effect (fig. 3).

Approaching the end of the outdoor concourse, we are invited to directly experience what it’s like to be on the ride, and in the world. Cast members–aka, DisneyWorld employees–encourage visitors to try out the unique design of the rollercoaster cars (fig. 4). Like the movies, one leans forward in these vehicles. A world of speed and risk is conjured, in immediately embodied ways. How are we safely secured in these cars? Just how safe are they?

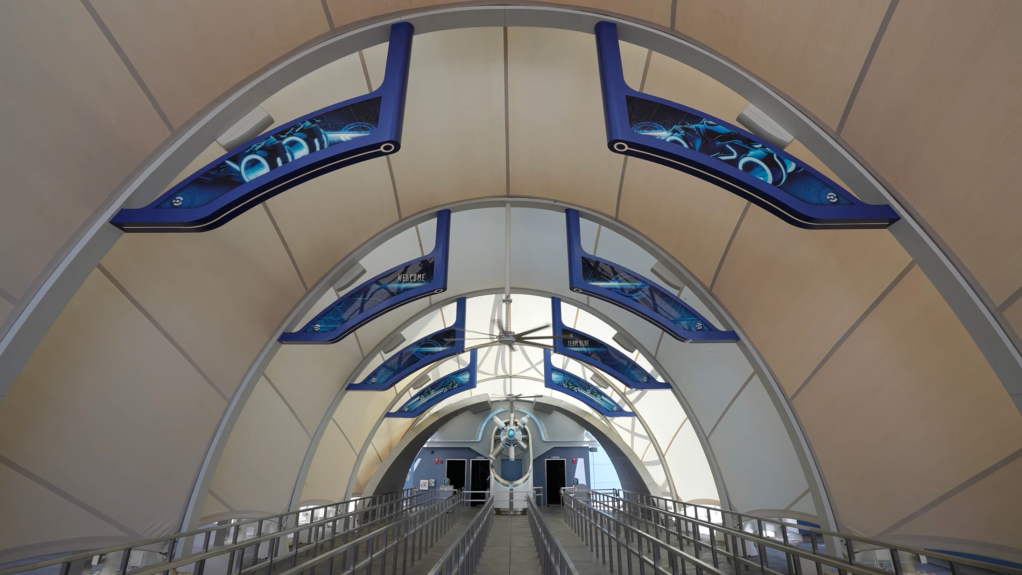

The outdoor portion of the attraction ends as we queue up beneath a symmetrical awning (fig. 5). Up above, signs on the left welcome us–an unusual cue for a DisneyWorld attraction. Questions–possibly ones with implications of plot–begin to arise. Why are we being welcomed? By whom? And why, on the right-side signs hanging above, are visitors referred to as “Team Blue”? More broadly, where are we in the TRON world? Who are we?

World-telling is beginning to modulate our experience. We’re being moved from a broad state of perspective-shifting (a general feeling that this space is tugging at us to imagine ourselves on these TRON vehicles) to a more fictionally inflected form of perspective-shifting, stimulating curiosity for the details of the world and our specific role in it. The fictional world’s culture and power relations invite attention now (i.e., this world is divided into teams, apparently, and if this ride is a race, perhaps we want our team to gain the upper hand).

Entrances matter in DisneyWorld attractions. They sometimes contain world-facts. A plaque above a door (fig. 6) refines our understanding of the characters we’re being invited to perform. We aren’t just on Team Blue. We’re users.

For visitors unfamiliar with TRON, the “user” reference is likely to evoke contemporary computer-speak; today we all use various technologies. But for visitors familiar with TRON, this term will mean something specific, returning us to TRON lore: the ride makes manifest a world where flesh-and-blood people who exist in “reality” can be digitized as game-playing gladiators and venture to an entirely virtual realm known as The Grid. This–a central premise of the TRON world–is introduced in both the original TRON (1982) (see the trailer below), reintroduced in the 2010 sequel film TRON: Legacy…

…and reintroduced again in the 2010 comic, TRON: Betrayal (fig. 7), a prequel to TRON: Legacy.

Once past the entrance, we move through a hallway lined with circuits (fig. 8)…

…and enter a tight, enclosed chamber where our bodies are to be digitized into the computer world. A logo appears on a massive video wall (fig. 9). I initially thought it might be a new badge for ENCOM, the TRON-world programming firm…

…but a nearby gift shop provides the answer (eventually, so does the ride itself). This is the logo for our virtual race team, Team Blue (fig. 10). At DisneyWorld, world-telling can go beyond attractions to include world-fact-reinforcing merchandise.

The video wall fractures into digital cells and “warps” us, as digitally simulated bodies, onto the Grid, whereupon the wall lifts and we witness the scale of the world–we see, through a window, a massive space containing a rollercoaster car of visitors preparing for their race (fig. 11-13). The abrupt shift from an enclosed room, facing a flat screen, to the sight of a wide open, three-dimensional TRON-world, I must say, induces a state of awe.

We leave the chamber and get a better view of the setting of the race (fig. 14.)

But this is only a glimpse. The attraction isn’t through with world-telling. The queue passes through a hall of opponents, with a screen mounted to the ceiling, featuring Siren (voiced by Faren Collins)–a version of the white-outfitted “preparation” programs who first appear in TRON: Legacy and are further developed in the animated series TRON: Uprising (2012-2013) (fig. 15).

This chamber plays a crucial role in the attraction’s world-telling. Siren further situates us in a power dynamic, reminding us that we’re in a high-stakes competition. “In a Light Cycle battle, there are winners, and there are losers,” she tells us. Nearby wall designs reinforce this; our competition in the race will be stiff (fig. 16-17). Opponents are characterized in rudimentary ways, through colors and mottos.

One wall design provides the attraction with a mythos–a past–too (fig. 18). Team Blue, we learn, has never won a race. The odds are against us.

A final wall design builds our confidence, however. With Siren’s guidance, Team Blue will be ready to compete, and perhaps win (fig. 19).

Siren announces: “Before proceeding to the synch chamber, all members of Team Blue must prepare.” She explains the rules of the game, visualized on a screen (fig. 20-21). Our opponents–Teams Red, Yellow, and Orange–will join us on the track. To defeat them, we must achieve an objective: we must pass through eight “energy gates” before the other teams.

Of course, this being a rollercoaster, the visitor has no control over the race’s outcome. We’re aren’t in a video game; the ride isn’t truly interactive. In fact, Team Blue always wins the race. But the visitor isn’t permitted to think that. The Siren chamber gives a very different impression. In the world of TRON, this is a serious race, and our opponents will give no quarter.

TRON Light Cycle/Run‘s world-telling is designed to establish mood. The visitor is continually made to feel unsettled. This rollercoaster is going to be unique–perhaps even a little dangerous. Heightening the visitor’s sense of urgency, the score composed by the French duo Daft Punk (click below), with its tightly knit electronic arpeggios, is fed through the attraction’s sound system. DisneyWorld is well-known for using sound to evoke emotions in visitors. In this case, Daft Punk’s beats tighten the abdomen; something challenging is impending.

Also heightening the visitor’s sense of urgency is an announcement–again, via Siren–that we must all check loose articles in a locker room. There is nothing comparable to this at DisneyWorld, giving squeamish visitors a rising suspicion that this ‘coaster may not be for them. As one might suspect, the act of checking bags and hats is constructed to immerse us in the TRON world. We ’round a bend, and the lockers are lit with TRON-style neons, with each door accessible only through one’s pre-programmed DisneyWorld wristbands or cards (fig. 22). We’re living in the future, now.

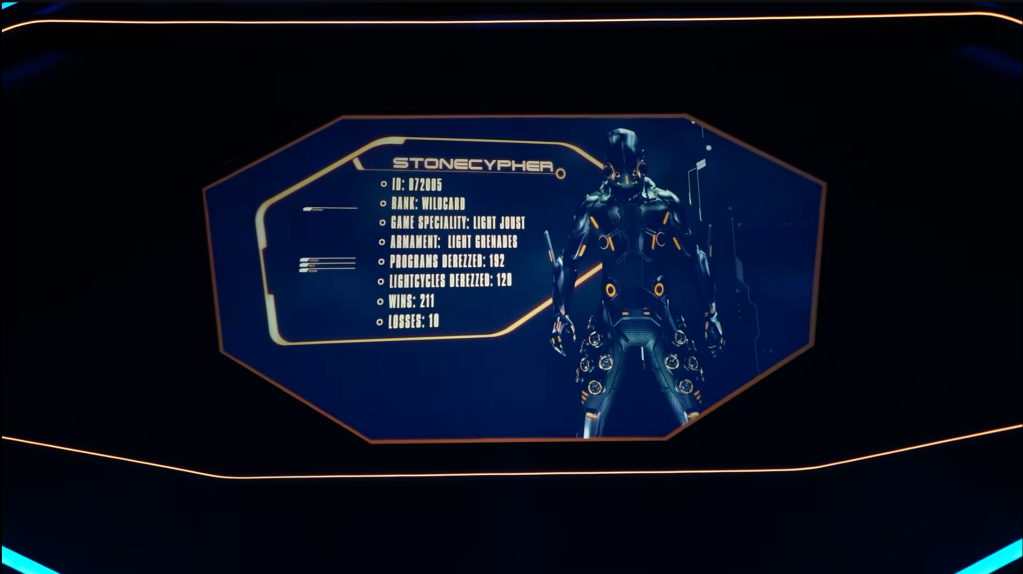

For the final phase of our–of Team Blue’s–“preparation,” we enter the launch room. A massive screen updates us on ongoing races and fills in more characters details, lending additional fictional weight to the premise that we are in for a high-stakes competition (fig. 23-25). Each team has members, and each member has particular skills and a history.

Notice that there’s storytelling here. By attending to the details of the world, and the actions we perform as visitors–looking, walking, pausing–we can build a simple causal chain: a) we are users of Team Blue whose bodies are digitized, b) we enter the Grid and prepare for a race, and c) we compete in the race.

But does the storytelling ever get more complicated than this? Does the story told here hook into TRON stories told elsewhere?

Initially, it seems not. By this point, no firm notion is planted in the visitor’s mind that events that transpire on TRON Light Cycle/Run will affect or develop particular events depicted in other TRON media. No plot events from the TRON movies are explicitly evoked; we aren’t directly or even indirectly asked to situate the circumstances of the ride within the TRON transmedia continuity.

Premises of the TRON world shape the experience, and in simple ways, are narrativized; but there is very little here–so far–to prompt us to think in terms of a larger causal chain of events. Winning the race, as far as we know, won’t affect the direction of the TRON narrative. Learning about these new characters–to be sure, ones found in no other TRON media–won’t bring the TRON continuity forward.

Or will it?

The rollercoaster ride itself is a pure thrill. After an initial pause and a countdown, the ‘coaster quickly accelerates through a brightly lit corridor (fig. 26), and ventures outdoors (fig. 27), reaching 60 mph (97 km/h)…

…and, after a few twists, enters a new chamber where something curious begins to happen. Screens running alongside the car (fig. 28) reveal the hazards of the competition. As we speed past Teams Red, Yellow, and Orange and through the energy gates, their cars crash–and their occupants derez (fig. 29).

“Derez” is a term evoked on the large screen of the launch room (see above, fig. 25). The character Stonecypher has hundreds of derezzed programs and light cycles under his belt. The concept, and the word, are part of TRON culture–a term for the “deresolution” (or “derezolution”) of a program. The program dies or dissolves or explodes from the Grid.

By the end of the ride, then, Team Blue hasn’t just won–its members have survived. Their digital bodies remain intact. Visitors leave their cars, and resume their real lives, off the Grid.

Here’s where TRON Light Cycle/Run begins to hint at a larger narrative payoff. As we exit the attraction, we are guided down a corridor which–in this fictional world–presumably exists in the “real world.” As such, the corridor reveals a whole new premise in TRON, a premise which implies a new link in the causal chain.

An entranceway announces an additional team–Team Green (fig. 30). No such team exists in the digital realm of the Grid, you’ll note. Furthermore, we are no longer on the Grid. So what is this team doing here? How come it exists off the Grid?

Note the sign–again, above the entrance. We’re again being welcomed, this time to join a team that forms in TRON’s flesh-and-bones realm.

Turn the corner, and the premise continues to evolve–again, through wall designs. Two characters never encountered before are profiled, in much more detail. A persona named Nexus is described as an “Innovation Director” (fig. 31). What’s that? we’re primed to ask.

Nexus leads the “Innovation Team” to “ensure maximum efficiency” of Team Green “User” technology. No such support team exists in other TRON media. No such support team has had to exists in other TRON media, and for good reason. No other TRON media brings Grid-like light cycles to flesh-and-bone reality. In short, no TRON story has ever given a character the capacity to ride light cycles in the human or user realm.

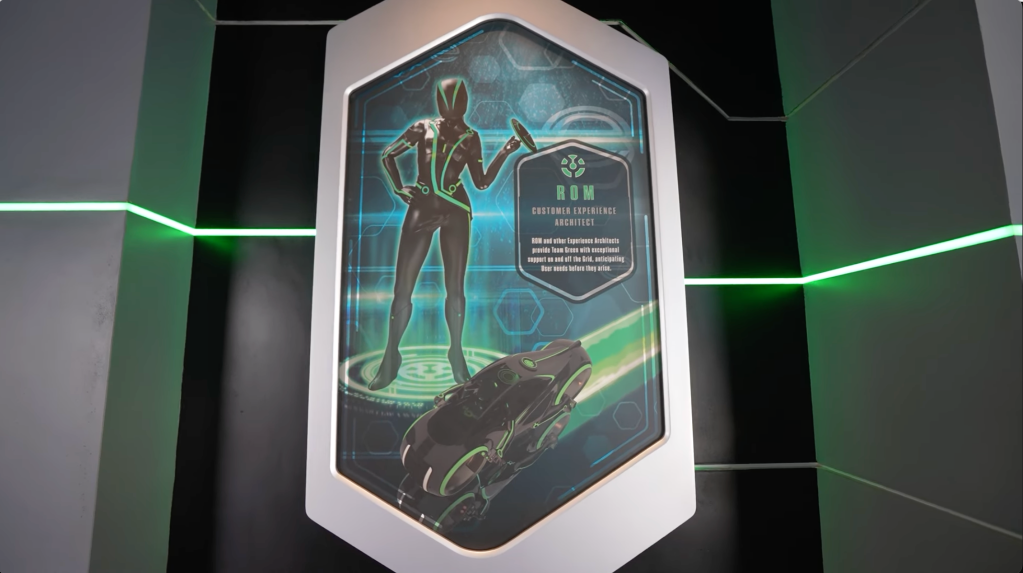

The second character is named Rom, described as a “Customer Experience Architect” (fig. 32).

Rom, it would appear, is a program who designs Grid-like races for users “on and off the Grid.” But when in the TRON narrative do programs start to serve this function, and when do races begin to take place beyond virtual reality?

Unlike a Disneyworld attraction I quickly referred to earlier, Avatar: Flight of Passage, the causality here isn’t explicitly provided. In Flight of Passage, a scientist informs us that the events depicted in the attraction are set a generation after the 2009 feature film, a revelation which provides a clear sequence of events for visitors. In the case of TRON Light Cycle/Run, we are presented with a narrative enigma, a question without an answer–an effect without a cause.

The final moments of TRON Light Cycle/Run sell us as users on the idea of light cycle racing in our world. This might be construed as a less-than-clever piece of branded cross-promotion; this space and the entire ride are sponsored by Disney corporate partner Enterprise, and the notion of technological innovation is inspired by Enterprise’s corporate philosophy. But all of that’s been embedded in the TRON world and its narrative. The crucial element for me is that this space doesn’t tell visitors how the TRON narrative gets to the point of needing characters like Nexus and Rom. A link in the causal chain is missing.

Here’s a hunch. With TRON Light Cycle/Run, the Walt Disney Company is beginning, in highly tentative ways, to create anticipation for the 2025 film sequel, TRON: Ares. Here’s how the film’s plot is described in recent reporting:

“[Jared] Leto will play Ares, the manifestation of a program that becomes sentient and crosses over into the human world, with [Greta] Lee as a video game programmer and tech company CEO who aims to protect her world-changing technology.”

Like the final moments of TRON Light Cycle/Run, programs will find a way to rise off the Grid and influence the “real” world.

This premise is anticipated in the 2006–2008 comic, TRON: Ghost in the Machine. This really trippy read, where the lines between real and computer world blur, culminates with the “integration” of a program so complex that its user–named Jet–invites it to leave the Grid, and live a life in the flesh-and-bone realm (fig. 33). The program declines.

Let’s close with a final thought about TRON Light Cycle/Run. On an official Disney site, Missy Renard, Creative Director of Walt Disney Imagineering, states the following about the Enterprise-sponsored space that closes the attraction:

“Team Green and their impressive Lightcycle’s programming are showcased throughout the space in dynamic displays that relay the incredible culture, capabilities and values of Enterprise – which make them uniquely qualified to join the competition. A single line of green light connects the displays as if to power up the Team Green stories in unison. Looking ahead, more stories about the twelve Team Green members will rotate through the display, providing returning Users an opportunity to enjoy even more Team Green stories on future visits to TRON Lightcycle /Run.“

I stress the important bit again: more stories. The narrative questions raised at the end of TRON Light Cycle/Run, it seems, will be refined over the coming years. Perhaps they will be sharpened, to fit the terms of TRON: Ares‘s plot as it continues to take shape.