This blog is about the art of the movies. But I’ve also commented here and there on style and storytelling in TV shows like Daredevil and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. As I have suggested elsewhere (here and here), professional wrestling ought to be of interest to film and media scholars, because the histories of wrestling, television, and film are often intertwined.

In this entry, I want to make a simple point: wrestling on TV deserves a place in any conversation about the successes and failures of modern serial entertainment. How so?

A new WWE documentary on Eric Bischoff, former president of the now-defunct league World Championship Wrestling (WCW), reveals the extent to which serial plotting drove the Monday Night Wars of 1995-2001, arguably the most lucrative period in wrestling history. The Wars were ultimately about viewership. How could WCW and its rival, the World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now World Wrestling Entertainment), generate ratings?

Crucial to Bischoff’s success was his ability to turn WCW’s flagship show, Monday Nitro, into legitimate competition for the WWF’s successful Monday Night Raw. Boldly, Bischoff, at the behest of Ted Turner (owner of WCW), aired Nitro head-to-head with Raw, and within a year, he became the only wrestling promoter to ever give WWF’s Vince McMahon a real run for his money (Nitro bested Raw in the ratings for 84 consecutive weeks). (McMahon ultimately won the war and purchased WCW and all of its remaining assets in 2001.)

At the peak of the Monday Night Wars, 10 million viewers were tuning in to watch the latest developments in the world of sports entertainment. (This past Monday, unopposed, Raw attracted just over 3 million.) What made Monday night wrestling so popular?

One factor that explains the wild popularity of the product in the late 1990s was its serial formula. We learn for the first time in the documentary that when Bischoff was given the go-ahead from Turner to launch his prime-time show on TNT, he devised a serial strategy for competing with the WWF–what he called SARSA.

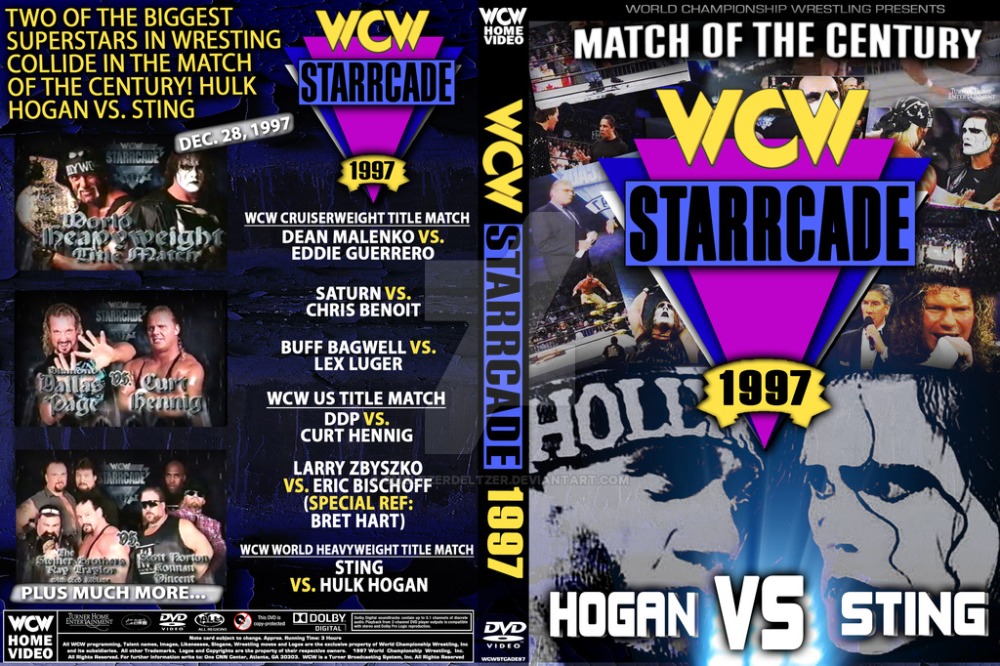

The acronym stands for Story, Anticipation, Reality, Surprise, and Action. Each component was intimately connected to the others. By Story, Bischoff refers to the need for wrestling shows to develop long-term serial arcs–plotlines that unfurl over the course of weeks, months, or even years. Perhaps the prime example of WCW’s long-form storytelling is the 14-month, “slow burn” toward the “Match of the Century” pitting antihero Sting against “Hollywood” Hulk Hogan, the dastardly leader of the invading faction, the New World Order (nWo), at Starrcade 1997. (A massive success, the pay-per-view event earned WCW its highest-ever buyrate.)

Reality (the creation of reality-based characters and a “live” feel on Nitro), Surprise (unexpected plot twists), and Action (the strategic use of in-ring and, for the first time in mainstream wrestling history, backstage conflict to introduce, develop, and resolve these narrative arcs)–all of these elements of the Nitro/Bischoff formula were critical to WCW’s extraordinary pop-culture success in the late 1990s.

I want to focus on Bischoff’s concept of Anticipation, for this is where, from my perspective, wrestling of the period has something to teach us about the power of serial storytelling. In developing his concept for Monday Nitro, Bischoff intuited that one of the most potent forces in our daily lives is our desire to look forward to things. To distract ourselves from the burdens of everyday existence, we “look forward,” he says, to “our birthdays” and to the holidays. A serial plot, he believed, should make use of events “along the way” that generate the sorts of pleasure we feel when we prognosticate–when we visualize these future events. Imagining the rituals that take place “down the line”–daydreaming about the very instant we leave for a long-overdue vacation or arrive at an annual reunion with childhood friends–structures our lives and boosts the spirit.

Bischoff’s folk-psychological hunch has merit. The very act of anticipating–of mapping out, however crudely, where a serial plot is ultimately headed–is part of what pulls us into a story. Wrestling promoters write their shows not only to create moments that prime this anticipatory hypothesis-formation; once they’ve taken steps to commit viewers to a series of prognostications, they can undermine them–create moments of Surprise.

The Sting-Hogan feud provides some useful examples. Over the long-term, Bischoff and his writers structured Nitro so as to “tease” the confrontation between these archrivals. Creating anticipation–being the source of speculation about the outcome–was the very raison d’être of the Sting character. He was written as a mute. It took some time to discern why this once-colorful and charismatic figure had morphed into a creature so dark, so brooding. Periodically, Sting appeared in the rafters of arenas, and announcers asked, what in the world does he want? As the story unfolded, he pointed his trademark baseball bat at Hogan, at one time a hero to millions but now a back-peddling coward who quivered in his boots. Sting, we learned, was seeking revenge. Anticipation created opportunity for surprise. In a twist, Sting appeared to join the nWo, and was shown at Hogan’s side. But it was all a ruse. As Sting got closer and closer to Hogan physically, viewers’ anticipation for the moment where Sting would strike only grew. When would he do it, and would he succeed in extracting his revenge, despite the odds?

Eric Bischoff had picked up on the basic psychology that drives modern serial forms. As Scott Higgins reminds us in his recent book, Matinee Melodrama: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial, literary critic and scholar Meir Sternberg understood anticipation–a reciprocal relationship between storyteller and viewer–as one of the fundamental tools of narrative:

In Steinberg’s model, the storyteller raises our interest in some future uncertainty and then delays closure, drawing out our anticipation. The reader’s task is to form hypotheses that might fill in the missing exposition, guided by the story’s limits on what counts as a “warrantable expectation.”

The legacy of wrestling serialism in the 1990s: perhaps better than the long-form storytelling of today’s Marvel, Star Wars, or James Bond franchises, “sports entertainment” storytellers understood the art of creating warranted expectations for what’s to come–of cueing viewers to ask, where is this all headed? and to reap the many emotional benefits.

Eric Bischoff discusses the documentary, his career, and the current wrestling scene on the latest edition of Jim Ross’s podcast.